Vigil

Eulogy written from the ashes of Bprrowed Time - a symposium on death, dying and loss, hosted by art.earth in 2021

'We’re all of us living on borrowed time: the brevity of our personal span of existence now mirrored by a biosphere under intolerable pressure, its every life system beginning to fray and unravel under civilisation’s weight. We witness its collapse every day now, in new stories of cataclysmic weather events, of lives lost, of flora and fauna weirded, disrupted, gone. However incipiently or unconsciously, we live at a time of collective grieving – no life exempt from the consequences of this relentless devastation and what it has set loose'.

– Borrowed Time: on death, dying & change, ed Richard Povall and Mat Osmond (art.earth)

Last November I took part in a series of events on death, dying and change called Borrowed Time. It was hosted by the Devon-based organisation art.earth who also collaborated with Dark Mountain's 'requiem' Issue 19. Following three lockdowns, and a year later than scheduled, the main gathering eventually took place online. And even though its subject was vast and unfathomable and usually observed with silence, deference, bound tight by tradition and form, the intimacy of the screen discussions brought us into a sudden and startling kinship. Each of us touched by our own and others' mortality in a way that felt both ancestral and entirely modern.

In response I wrote the following text to capture of some of their mood and existential attention, accompanied by artwork from the Dark Mountain edition. The book is a gathering and celebration of the voices, images and creative practice made in the wake of the symposium by organisers Richard Povall and Mat Osmond.

Mortuary

Somewhere a vigil through the long dark night is being held, while most of us are sleeping. While most of us have our eyes on the road, Kathryn Poole alights from the bus to Stockport, her eye caught by the flapping of a dead owl’s wing in the tailwind, as if it were still alive. She will render the speckled feathers in pen and ink as a memorial. While most of us neglect the cost of toil on human bodies, Tom Baskeyfield enters a mortuary on the side of a Welsh mountain, and puts his hand on the cold slate slab. He will render the stone on paper with graphite, stippled with the lives of the men who died while mining this slate, and once were laid here. While most of us avert our gaze, forests are disappearing, the animals are leaving, the seas are emptying, our hearts are yearning without knowing why. No canvas seems large enough to hold it.

Kathryn Poole. Death Throes.

Shroud

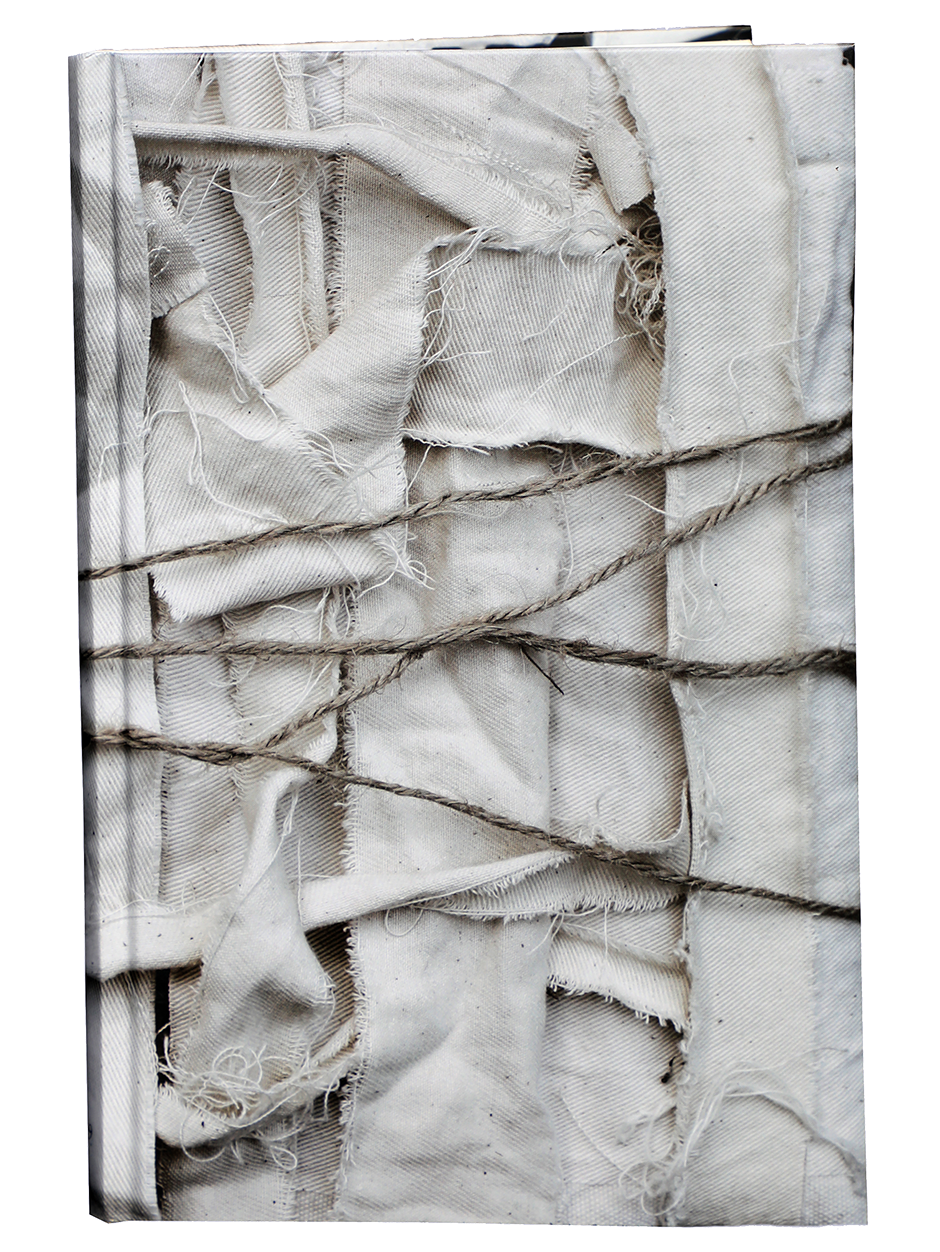

Caroline Ross. Grave Goods (detail)

On an island in the Baltic that is the last matriarchal community in Europe, women in flowering dresses gather around a casket in the dead woman’s kitchen, to pray and sing and mourn. In Armenia, the academic told us, where the villagers also once gathered in each others’ rooms to bid farewell, there are now specially built funeral houses. Grief is no longer a shared thing among the community, but an individual concern. A quiet has prevailed, where once there were tears and sorrowing.

We gathered as if in these old kitchens, learning over tables, looking into each other’s faces. sharing prayers and blessings, in the spirit of the vigil. We spoke of the dead. We found that there are still women in our own land who stitch their own grave goods boots from deerskin, decorated with oak gall, who provide felt blankets to swaddle the dead before they go back into the cold ground.

Who will wrap us, who will sing for us? Who will remember our passing through? The warmth we once held?

Who will keep vigil for us in the dark night as it approaches, keep the fire of the world alight?

Memoir

I am writing this from memory, long after the gathering that was the Borrowed Time symposium last November. I am remembering, because time doesn’t go in a straight line, like history. To bring renewal to the world it needs us to loop and feed back, in gardens and culture.

In her memoir about grief and mourning A Year of Magical Thinking Joan Didion realises her cataloguing everything about her relationship with her dead husband was an attempt to reverse time, to stop the forty years of living closely from disappearing into a black hole. Her fearless remembering of the minutes and years, are a writer's capacity for finding moments that are like keys to a closed door: significant because they reveal the life that counts, our presence here together. What remains when you take away the issues, the opinions, the thoughts and numbers, that whirl about in our heads. What really matters.

I lit a fire, she said, I closed the curtains. He praised my work. We swam with the tide into the cave at Portuguese Bend, You had to feel the swell change. You had to go with the change, he said.

Tumulus

Sometimes I go to sit on the tumulus down towards the Blyth river. Crowned by silver birch and rowan trees, it houses the dead from hundreds of years ago. Why is it that these archaic places feel like a solace, an anchor in rocky times? Not my kith lie buried here, but my kin. People who lived close to the land, and these ancestor trees, the deer, the lichen on the rocks. My body, my blood. Once we waited here at winter solstice for the light of the new sun to fall into the chamber, holding our breath, the breath of the year.

How can I value my life, if I do not have the dead close to me? Who else can take us back down into the kiva and kur, where all life and regeneration begins, to remind us of our obligation to give back.

Wake

I made a book of the dead with fellow writers, wrapped in a winding sheet. In it we placed the keening of birds and people, these staffs with hands that clasp the wind, the flowers that light the way to the Underworld. Everything I write, my body, my intelligence is compost for the future, said the poets. We are a nurse log for the new, happy to sit in the dark with you, doing this work, not knowing what comes after.

It is a mood and an attention that is held in these encounters, because the dead, our kin are in the room, because with this relinquishment, the fierce joy of remembering the presence of living beings comes to us. The memory you keep treasured in the heart’s locker for others to stumble upon.

What does the mind remember? A grinding sound, keeping the machinery of an illusionary world in place, an ancient hostility, distracted by a fast-flickering screen.

What does the writer remember? The shape and colour embedded in stone, leaf, skin, lichen, the sound of water, the curlew calling from the river, your voice. This library of Earth, sunlight held in matter.

The great mystery of Earth is time, said the blind writer, holding a book in his hand.

We borrowed it, and forgot to bring it back.

Our return is overdue.

Borrowed Time: on death, dying & change, ed Richard Povall and Mat Osmond is published this month by art.earth